In the beginning was the story. And the story told us what people did. And the story told us how we should act—what we should and should not do. The story put right and wrong in the context of what people did and what was done to them.

In the beginning was the story. And the story told us what people did. And the story told us how we should act—what we should and should not do. The story put right and wrong in the context of what people did and what was done to them.

After Elohim creates the heavens and earth, Adam and Eve wander through the Garden of Eden. The serpent entices them to eat the forbidden fruit, whereupon Elohim banishes them from the Garden. That explanatory myth carries a lot of weight in the moral system of the people who heard it thousands of years ago and retell it today.

Right after that story, we hear the story about Cain who was jealous of Abel and killed him. Elohim banished Cain. That story transmits the implicit injunction: Don’t murder people. If you do, the consequence is expulsion from human society.

The first book of the Hebrew Bible is nothing but stories, all with moral import. We don’t get to the Ten Commandments until Exodus, the second book.

In another culture, people are listening to poets tell about Achilles and Agamemnon in the Trojan War. Agamemnon has stolen Achilles’s war prize. What Agamemnon did was not right. Achilles knows it wasn’t right. Agamemnon does too. And so do the listeners. Achilles goes to his ship and refuses to continue fighting. Things go poorly for Agamemnon and the other Greeks until Achilles rejoins the war. Thousands of Greeks learned numerous moral lessons from listening to the Iliad again and again.

Children eagerly ask for stories. Parents read them. Moral lessons are absorbed.

Children eagerly ask for stories. Parents read them. Moral lessons are absorbed.

To the simple stories of childhood, our culture adds great novels, plays, and movies. Moral complexities and challenging moral dilemmas are presented the way they are encountered in real life. We wrestle. We discuss. We debate. We reach conclusions. All of this becomes part of our cultural property (Kulturgut), that which makes our group distinctly our group.

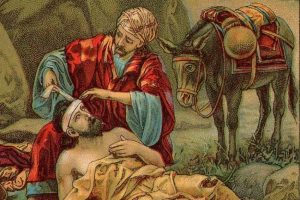

A lawyer asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus replies with a question: “What is written in the law?” The lawyer responds, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind and your fellow tribesman (neighbor) as yourself.” When Jesus says that the lawyer has answered correctly, the lawyer, seeking to pin Jesus down, asks: “But who is my fellow tribesman?”

The lawyer may have expected Jesus to provide an explanation from the law, based on genealogical relationships. Instead, Jesus tells him a story about a man who was beaten and robbed on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho. A priest and Levite–fellow tribesmen of the victim–passed by on the other side of the road. A Samaritan–a member of a group despised by Jesus’s audience–stops, tends to the victim’s wounds, brings him to an inn, and pays the innkeeper to take care of him. At the end of the story, Jesus asks, “Which of these three showed himself to be a fellow tribesman to the man who was beaten and robbed?”

relationships. Instead, Jesus tells him a story about a man who was beaten and robbed on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho. A priest and Levite–fellow tribesmen of the victim–passed by on the other side of the road. A Samaritan–a member of a group despised by Jesus’s audience–stops, tends to the victim’s wounds, brings him to an inn, and pays the innkeeper to take care of him. At the end of the story, Jesus asks, “Which of these three showed himself to be a fellow tribesman to the man who was beaten and robbed?”

The story of the Good Samaritan conveys the point that love transcends tribal (or party or country) boundaries more succinctly and powerfully than any form of legal discourse ever could.

In The Literary Mind, Mark Turner argues: “Story is a basic principle of mind. Most of our experience, our knowledge, and our thinking is organized as stories. The mental scope of story is magnified by projection–one story helps us make sense of another.” Our minds are built for stories. Stories are how we think and communicate.

Stories entertain, yes. But they also educate. They contribute to Bildung, cultural maturation. They are particularly good vehicles for conveying moral content, for presenting moral problems and solutions. Stories are the first and best ways we have to explore moral ambiguities and the complexities of moral decision making.

Had we nothing but our collections of stories, we would learn how to distinguish right and wrong in real life. Values, virtues, and norms would eventually emerge, but they would be shaped by and in turn shape our stories.