What is important? What should be important? Why should it be important? Can we justify what we believe is important in terms of something else?

What is important? What should be important? Why should it be important? Can we justify what we believe is important in terms of something else?

These are value questions. The noun “value” refers to what we consider important or what, in fact, functions as important in our decisions and the ordering of our lives and interactions with others.

Indeed, little written on the subject helps us understand what the word “values” means or how it functions in the mental life of humans. This is true in popular speech as well as much of the philosophical literature. As a result, much of the discourse on Family Values, Christian Values, Human Values, Scientific Values, and the like sheds little light on the underlying subject. Those speaking or writing appear to assume that everyone knows and agrees what these values are or, indeed, what it means to refer to values. I believe that assumption is unwarranted.

The root of the problem may be that in much of the conversation, people speak and write as if values (what is or should be valued) have an independent existence from valuing minds. Some external authority, including such as a philosophical school or a divine being, tells us to value X more than Y. In this way, what we should value–values–is supposed to be absolute, unconditional, not subject to debate, not a human choice.

To the extent this observation is correct, the search for values in Western philosophy suffers from the same basic flaw as the search for an absolute foundation for morality generally. It presupposes that whatever satisfies that search exists apart from our own mental activity, that is, that we did not create it.

In a short essay published in 1957, Paul Tillich wrote, “Our knowledge of values is identical with our knowledge of humans, not our knowledge of their existential but rather of their essential nature.” (“Is a Science of Human Values Possible?”) Tillich’s essay seems to be in the service of an attempt to figure out how to go about determining what we should want, what our values should be. Before we get to that point, however, we need a psychology of values and valuing.

In a short essay published in 1957, Paul Tillich wrote, “Our knowledge of values is identical with our knowledge of humans, not our knowledge of their existential but rather of their essential nature.” (“Is a Science of Human Values Possible?”) Tillich’s essay seems to be in the service of an attempt to figure out how to go about determining what we should want, what our values should be. Before we get to that point, however, we need a psychology of values and valuing.

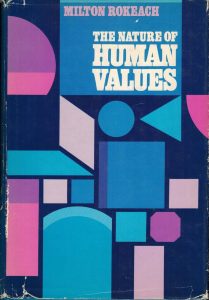

Milton Rokeache’s book, The Nature of Human Values, constitutes a major exception to my general broadside against most discourse on values in the English language. First published in 1973, the book is a straightforward psychology of values as the process of valuing, including the roles values play in human behavior. I have not found anything remotely like this in the philosophical literature.

In this section of the website, we will point out where discussions of values are occurring and develop examples of the topics covered in Rokeach’s book. We will grapple with the greater conversation about values and the role they play in moral systems; for what we hold dear, what is important to us, unquestionably plays an important role in the effort to distinguish right from wrong.