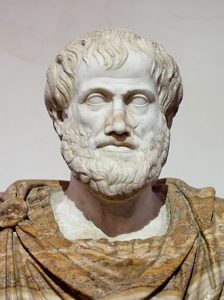

Moralists have warned about the Seven Deadly Sins since John Cassian first listed them in the late 4th Century C.E. In Western Civilization, attempts to identify virtues and the virtuous life go back at least to Socrates and probably before that, with Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics being one of the most famous presentations of virtue ethics. Confucian Ethics is a virtue ethics developed in the Chinese Civilization.

As elsewhere on this website, our objective is not so much to discuss the writings of philosophers and religious leaders–important as they are–as it is to explore how we wrestle with what counts as virtue (and as vice) over time and why. Some virtues endure. Courage is extolled today as it was in Aristotle’s time, though the focus on what counts as courage may have changed. Do we still count piety among the signal virtues the way Medieval leaders reportedly did? Perhaps not. If not, why not?

How do we distill virtues? How do we settle on vices?

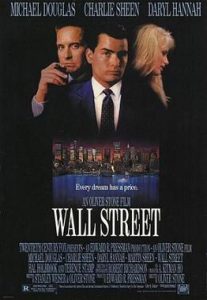

What effect does the open flouting of received virtues and the flaunting of established vices–as in the behavior of Donald Trump and other infamous celebrities of the Second Gilded Age–have on our moral sensibilities? Will their effect drain off into the sewer of excess? Or will our children come to believe with Gordon Gekko, the notorious character in Wall Street, that “Greed is good?”

This too is part of the Great Conversation About Right & Wrong. Like the identification of heroes and villains, the waxing and waning of our notion of virtues and vices affects our moral system–what people actually do and refrain from doing. And in this way, our thoughts about virtues affect the quality of our societies.